Through the twists and turns of fate, Conrad Bongard left an indelible mark on Prince Edward County.

Life plans Interrupted

Born Johann Konrad Bangert in 1751 in Lohrhaupten, Germany, he was a linen weaver (Leinweber) by trade. At 160 cm (5'3") in height, his lack of stature was overshadowed by his grit and determination, characteristics that ultimately preserved his life.

Conrad was not destined for a secure life as a tradesman -- he was among 30,000 young German men who were conscripted into military service in 1776, to serve as auxiliaries to the British Army during the American Revolutionary War. In Conrad’s home state of Hesse-Cassel, leasing soldiers to other countries was a major source of government income. The German Auxiliary forces, known as Hessians, were among the most formidable in the world -- reputed as tough, well-trained, and valued for getting the job done.

During the American Revolution, 1,200 German auxiliaries died in battle and over 6,000 died from disease. At the end of the war, 17,000 returned to Germany, but 5,000 chose to stay in North America.

Farewell to homeland and family

The Hessian military training and discipline was brutal, molding the men into powerful soldiers capable of withstanding some of the harshest conditions. They were schooled in European warfare, drilled constantly and endlessly conditioned. Men could be hanged for leaving their post and their families would also be punished for their misconduct. These stiff penalties resulted in the most disciplined army in Europe.

Conrad trained as a cannoneer with the Hesse-Hanau artillery. The roar of the artillery eventually caused him to lose his hearing.

Hesse-Hanau artillery

When the troops departed Germany in 1776, this was Conrad’s final farewell to his homeland, his ageing parents, a brother and two sisters. The march from Germany to England was the first leg of a long and arduous journey to reach America. His regiment embarked from Portsmouth, England to sail across the Atlantic to Canada. The perilous transatlantic crossing took about six weeks, dependent on the wind and weather conditions. The journey across the ocean was difficult. The men endured weeks of sea sickness, cramped quarters, and unsanitary conditions replete with spoiled food and water, scurvy, swollen legs, the itch, fevers, rats, and high tensions. They finally arrived in Québec to join the British army.

They disembarked with mixed expectations. The troops were poorly informed, they had been told very little about the colonies or the aims of the expedition. What they knew about America came mostly from rumours. Most of the men had never been outside their own small village, and few had ever been outside Germany. In this new land they were homesick, frequently ill, surrounded by foreigners who spoke English and French, engaged in a strange war, and longing only to return home alive.

Sent to the front lines of battle

While most of the Hesse-Hanau regiment remained in Canada to protect the border in present-day Québec and Ontario, a portion of their soldiers including Conrad were sent to engage in active combat in the Colonies.

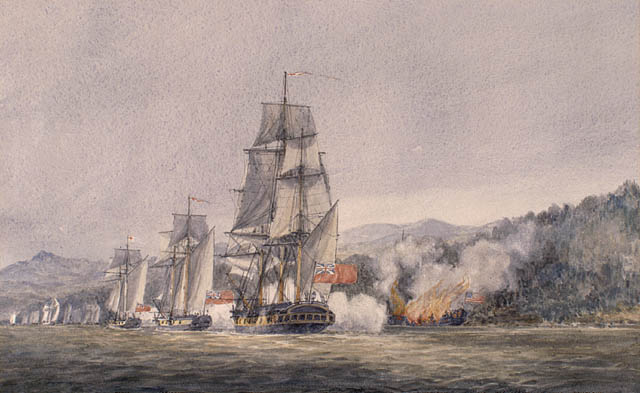

Conrad’s Hesse-Hanau artillery division fought in the naval Battle of Valcour Island (located on Lake Champlain in New York) in which most of the ships in the American fleet under the command of Benedict Arnold were captured or destroyed. This victory was followed by the successful takeover of Fort Ticonderoga, widely believed to be virtually impregnable and a vital point of American defence.

Battle of Valcour Island

Their fortunes of war turned in October 1777, in Lieutenant General John Burgoyne's Saratoga campaign. Vastly outnumbered by the American force, Burgoyne was forced to surrender. The British and German troops he led were kept in captivity until the end of the war in 1783.

“Surrender of General Burgoyne” by John Trumbull

Prisoner of War

The 2,139 British, 2,022 Germans, and 830 Canadians who General Burgoyne surrendered at the Battle of Saratoga in October, 1777 were not supposed to end up as prisoners of war. The terms of surrender included shipment to Britain, but the newly formed United States of America Confederation Congress voided the deal.

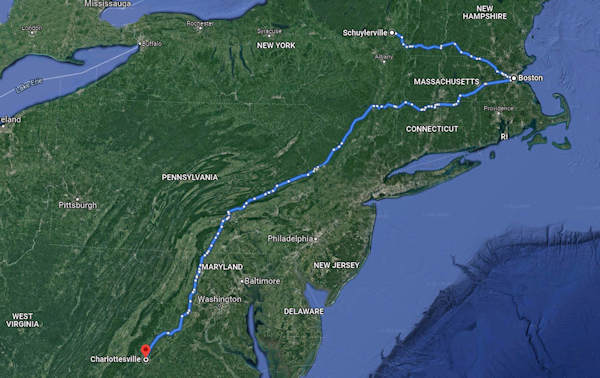

The Saratoga campaign and surrender took place near present-day Schuylerville, New York. Those soldiers were, over the next five and a half years, forced to march 1,100 miles (1770 km) between prisoner of war camps in Massachusetts, Maryland and Virginia.

When the troops arrived during winter at Albemarle camp in Charlottesville, Virginia, the German prisoners had to build their own log shelters. Some of the troops deserted to the Americans, especially when food supplies ran low because the British quit paying the bills when the troops were sent to Virginia. At the time of the American Revolution, nations were responsible for providing supplies for their prisoners. Others managed to escape and get back to the British base at New York City. Roughly 85% of Gen. Burgoyne's army died from disease and starvation, or deserted and started a new life in America.

Conrad attempted to escape in 1780 but was recaptured. This didn’t daunt him for long, he escaped again and successfully made the long trek back to New York to the British lines. He had to be resourceful in order to remain hidden from the rebel Americans and to find food and shelter along the way. Adding to the difficulty was his thick German accent that prevented him from easily blending into the American population. From New York he traveled by ship back to his regiment in Quebec.

Ordered back into military service in Germany

The end of a war should be a relief. However, when the American Revolution was over In 1783, most of the Hessian soldiers went home to Germany to be called to fight in another war in some other place. Conrad applied for permission to remain in Canada but that was refused by his commander because he was a subject of the Hesse-Hanau Prince. Bangert deserted on 1 August 1783, the day of embarkation of his regiment to Germany.

Harsh weather, defeat, and imprisonment were not enough to dampen his affection for the New World way of life. His home state of Hesse-Cassel and the other central German provinces were landlocked, densely populated, and over-farmed. He could envision greater opportunities in Canada.

Settling in Marysburgh

After release from his desertion, Conrad became the servant of surveyor Holland and together they surveyed up the St. Lawrence and much of the first four townships in Prince Edward County.

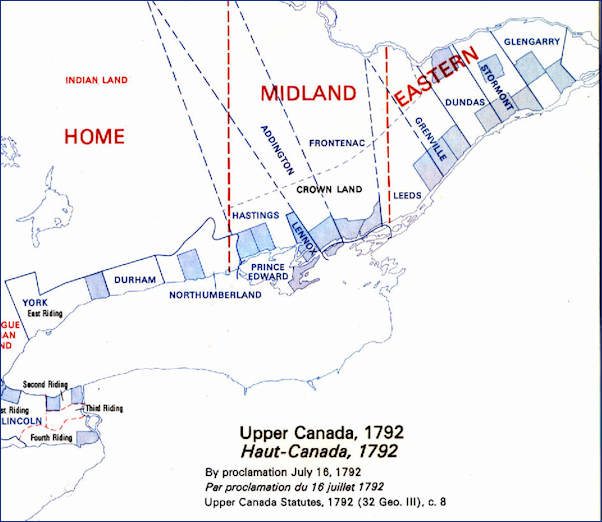

Meanwhile, several thousand of the troops and United Empire Loyalists were assembling at Sorel in Lower Canada (now Quebec). They had been granted land in Upper and Lower Canada for their loyalty to the British Crown and were awaiting passage in the spring of 1784 to their designated areas. As an NCO, Conrad was entitled to a land grant of 500 acres in Marysburgh in Prince Edward County.

Before their departure from Quebec, Conrad married a widow Susanna Victoria Houseman Carr/Kerr at the Holy Trinity Church in Quebec City. Susanna’s first husband had died as a prisoner in Virginia and may have been imprisoned with Conrad.

Under the leadership of officer Baron Gottlieb Christian von Reitzenstein, 29 men, seven women, and eight children destined for Marysburgh undertook the arduous trip along the Saint Lawrence River from Lachine to Cataraqui, today called Kingston. The morale of the group sank when they had to endure several more months in Cataraqui because their land in Marysburgh was not yet surveyed. When they finally reached the area allocated to them on October 4th, 1784, there was just enough time to erect makeshift cabins to shield them from the harsh winter.

The hunger years

The British government supplied rations to the settlers for the first three years, dispatched out from Montreal. The remote settlement of Marysburgh was the last depot along the delivery route, by which time the supplies were largely depleted. Baron von Reitzenstein incessantly advocated the cause of the settlers to the representatives of the British Crown, getting as far as the governor. However, his requests were not answered, and his stake of almost 1500 acres was seized when he went into debt to help the other settlers. He subsequently left Marysburgh and headed to Quebec, where he died in 1794.

It took a few years for the Hessian settlers to become self-sustaining, as the densely forested land had to be cleared before they could farm it. They learned how to fish and make maple syrup from the “Indians”. The year of 1787, after the rations stopped, is known as “the hunger year” when many starved to death.

Pioneers

In this undeveloped wilderness, it was hard to maintain communications with the outer world. Usually in the fall of the year settlers joined with neighbours in chartering a small vessel to Kingston. They brought the produce of their farms, for which they bartered for clothes, boots, harness, etc. Sometimes when it was difficult to get shoes, they made crude shoes from tanned leather from the hide of an ox.

At the time of his daughter Christiana’s birth in 1788, Conrad and Susanna had a cow, a team of oxen for tilling a few acres of partly cleared land, a settler’s and soldier’s right to about 500 acres of primeval forest, well stocked with deer, wolves and other wild animals. Sheep, pigs and horses were not yet introduced.

Bongard’s Corners

The spelling of Johann Konrad Bangert’s name gradually changed to Conrad Bongard. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the spelling of names was based on sounds and therefore varied greatly. Examples of other local Hessian names that became anglicized are Minaker (from "Meinecke/Moennecke"), Smith (from Schmidt or Schmitt), Hineman (from Heinemann/Hinerman/Hinderman), Snider (from Schneider).

Shortly after their arrival in Prince Edward County, the settlers built a small Reformed Lutheran church in Waupoos from beams and lumber floated over from the government sawmills at Cataraqui. The Bongards of Marysburgh possessed a copy of the bible in the German language and a Lutheran minister named Meyers conducted services. By the turn of the century the population of Bongard’s Corners had reached 150 and a post office was opened in 1843. This community was among the first German-speaking settlements in Ontario.

Customs of the Fatherland

Although loyal to the British crown, Conrad prided himself on preserving the customs of the Fatherland. He continued to speak English with no great concern as to its accuracy and this was characteristic of his children after many years of association with those who spoke English. His son-in-law, Wm. Williams, recalled that the absorbing topic of conversation at the wedding breakfast was concerning the best way to make sauerkraut!

Conrad's daughter Christiana received some education, enabling her to read in both the German and English languages. Her teacher was the Lutheran minister Meyers.

Rose House

Christiana Bongard married a British Loyalist, Peter Rose. Peter bought a plot of land next to the old Lutheran church and upon their marriage Christiana received 60 acres of land adjacent to this property as her dowry. Here, Peter and Christiana used the pine wood from the remains of the old church to build their farmhouse, where they raised 11 children. Described as the gem of Waupoos, Rose House has survived since the early 1800s with few alterations, inhabited by several generations of the Rose family. The Rose House has been a museum since 1964.

Rose House Museum in Waupoos

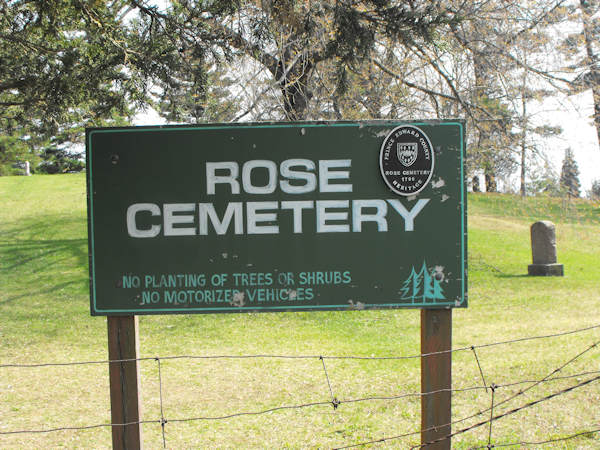

The Rose Cemetery located near Rose’s house contains the remains of most of these first German settlers. Hessians were initially granted the status of U.E.L. United Empire Loyalists, but this was revoked in 1802 by order of the Lieutenant governor of His Majesty’s Province of Upper Canada.

Conrad’s legacy

Despite a life of hardship, Conrad survived to the age of 89. At the time of his death in 1840, he left behind his widow, 9 children, 84 grandchildren, and 65 great-grandchildren, in all 158 living at that time. Seven generations later, his descendants now number in the thousands.

Conrad’s descendants have helped to shape Prince Edward County and Canada by their contributions as farmers, fishers, teachers, doctors, builders, sailors, entrepreneurs, lighthouse keepers, township councillors, a County Treasurer, a captain in the War of 1812, a Canadian diplomat and too many more to list.

Along his life’s journey, Conrad helped to establish one of the first German-speaking settlements in Ontario. Permanent markers of his presence include the survey work along the St. Lawrence and in Prince Edward County, the Rose House Museum and Rose Cemetery in Waupoos, and Bongard’s Crossroad.

As author, historian and Hessian descendant Jean-Pierre Wilhemy put it best:

"And so, generations pass, taking with them into oblivion the memories of their forefathers' hardships, hopes and freedom. New generations are left with only a surname for a legacy, a name whose spelling time has reshaped more than once, camouflaging the country of their origins and their ancestors."

Epilogue

As one of Conrad’s many descendants, I am thankful that he persevered and settled in Prince Edward County. He would undoubtedly be surprised at the transformation of the local landscapes – this area is no longer thickly forested, and about 25,000 settlers now call this home. However, the County's strong sense of community and independent spirit are still very much evident.

If your family is of Hessian descent from Marysburgh, please be sure to get in touch anne@countymoments.ca. I'd love to hear from you.

Hello !

I was reading some work from a cousin about Hans Bangert -> Peter -> Johann -> Conrad and thought to google “Bangert Bongard”. This took me to your site.

I’m in Webster, NY along Lake Ontario.

Thank you for your work.