Did you ever imagine that the bold Highlanders, donning their kilts, were some of the earliest European pioneers in Prince Edward County? Even after over two centuries, their family names remain familiar, etching their mark on the County's history.

In a time when history's tapestry was woven with threads of tradition and rebellion, a Highland custom faced suppression. The wearing of the kilt was deemed unlawful within the British Commonwealth. The consequences were severe, with imprisonment for the first offense and banishment to distant colonies for the second. This stringent ruling, established by the British Act of Proscription in 1746, aimed to subdue the unruly Scottish clans and incorporate them under governmental control..

Curiously, British soldiers were granted an exemption from this decree, a tradition inherited from the esteemed Black Watch regiment.

Amidst this backdrop, the 84th Highland Regiment marched gallantly into history, adorned in their iconic Highland uniforms, complete with plaids and swords. While the name implies a solely Scottish composition, this regiment was composed of about 25 percent Scottish soldiers, the remainder hailing from various corners of the English Colonies.

Their valorous experience was a cornerstone in safeguarding the lands that would eventually become Ontario, Quebec, and Atlantic Canada during the tumultuous times of the American Revolutionary War.

The echoes of battle and bravery eventually subsided, and as the curtain fell on the Revolutionary War, the "old 84th" unit was disbanded. Yet, the flame they ignited continued to burn, finding its manifestation in the Stormont, Dundas, and Glengarry Highlanders, a unit perpetuating their legacy in the Canadian Army.

From Battleground to Homestead

With the Highland warriors’ spirits still soaring, many of these kilt-clad soldiers transitioned into a new role – that of settlers, farmers, lumbermen, and fishermen in the picturesque surroundings of Prince Edward County. Their resilience and resourcefulness were the cornerstones of their new lives, carving out their destinies amidst the verdant landscapes.

At the close of the American Revolution in 1784, the proud 84th Highland Regiment faced a crossroads in their lives. Disbanded and with their battlefield days behind them, many of these resolute soldiers found themselves drawn to the promise of a new beginning. Nova Scotia and Eastern Ontario welcomed these resilient veterans, granting them land as a token of gratitude from the king. Their mettle, honed on the battlegrounds, would serve them well as they embarked on the challenging journey of pioneering a fledgling nation.

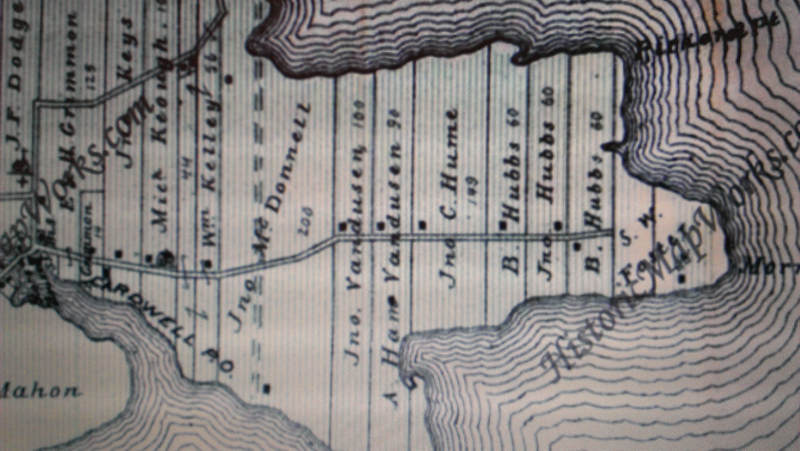

One such band of retired Highlanders embarked on their journey in the autumn of 1784. A flotilla of flat-bottomed boats, known as bateaux, carried these intrepid souls to the shores of Prince Edward County. Led by the indomitable Lieutenant Archibald MacDonnell, they anchored their hopes and dreams at the heart of MacDonnell’s Cove—a haven nestled along the eastern expanse of Pleasant Point, a name etched in history as Prinyer's Cove.

The untamed wilderness of the "5th township," now recognized as North Marysburgh, awaited their touch. An untouched tapestry of nature stretched before them, cloaked in a dense forest that whispered tales of both challenge and opportunity. With no roadways to navigate, waterways and footpaths became their lifelines, connecting them to their past and leading them into the unknown tapestry of their future. The echoes of their footsteps marked the arrival of pioneers, destined to leave an indelible mark on the land they now called home.

As the first winter enveloped the land, the men who had ventured to these untamed shores found themselves grappling with hardships that tested their mettle to its limits. Inadequate clothing, shelters that offered meager protection, tools that had yet to be forged, and scant sustenance painted a grim portrait of their initial struggles. The letter crafted by MacDonnell, penned on the 20th of September in 1784, captured the desperate situation in poignant detail.

“The British disbanded Troops … will in cold be reduced to the greatest distress, for want of clothing; some of them have not even a blanket to cover them from heavy rains & pinching frost, or to hold out the damp of the ground they lie upon. Another object of great consequence to them, is the want of a blacksmith to make & repair their axes, hoes & agricultural implements. They are a great distance from any immediate relief, some of them at thirty miles distance by land, exclusive of three miles of water.”

As if echoing their struggle, the words of Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce Lahontan took on new resonance: “To survive the Canadian winter, one needs a body of brass, eyes of glass, and blood made of brandy."

With unwavering determination, MacDonnell and his men wielded axes as they carved their dreams onto the untamed canvas of the wilderness. Land once shrouded in a thick blanket of trees was now cleared for the toil of farming, while logs that once reached for the sky were repurposed to fashion fences and cabins.

In their wake, roads emerged like lifelines, slicing through the dense woods and revealing pathways to a future yet uncharted. MacDonnell himself became a driving force, his vision stretching beyond the horizon as he toiled not only as a pioneer but as a magistrate, militia officer, and lieutenant of the burgeoning County.

More than 2,000 acres of land unfurled beneath MacDonnell's stewardship. In Marysburgh, ship's carpenters employed their skill to give rise to his log house that would stand as a silent sentinel for over a century. The log house passed into the hands of Elizabeth MacDonnell, his niece, who in her union with John Prinyer lent her name to the cove where their story intertwined.

Prinyer's Cove, a name echoing across centuries, stood as a haven for more than just aspirations. In the tapestry of the 1800s, it was frequented by commercial schooners seeking refuge from the tempestuous lake squalls. Docks welcomed vessels laden with supplies, lumber, fish, and eventually barley — an ever-changing tableau of commerce and community in tandem with the ebb and flow of the waters and time.

Though the Revolutionary War had faded, the frontier land remained a theatre of tension and strategy. Close to MacDonnell's Cove, a pivotal episode unfolded — one that would etch the name of Captain John Prinyer in the annals of bravery. Tasked with a daunting mission, Captain Prinyer found himself facing the stark reality of outnumbered odds as thirteen armed American soldiers made their incursion into British territory.

With only a small band of four men at his disposal, the odds seemed insurmountable. Yet, Captain Prinyer possessed something far mightier than numbers — his keen understanding of his adversaries.

The American soldiers, accustomed to the comforts of a more "civilized" existence, found themselves venturing into the rugged terrain — a world starkly different from their own. Their steps were haunted by the specter of the unknown, and whispers of the "natives" carried an aura of apprehension. Captain Prinyer, attuned to these nuances, seized upon their vulnerability, employing a plan that hinged on their lack of familiarity with the wilderness.

Prinyer dispersed his small band throughout the dense woods, each stationed to mimic the haunting war cry of the First Nations. This ingenious ruse plunged the American soldiers into a state of disarray and apprehension. As their camp was enshrouded by the eerie echoes, Captain Prinyer seized the opportune moment. With unwavering conviction, he strode into the American camp, casting himself as a saviour rather than a foe.

With silver-tongued persuasion, Captain Prinyer spun a tale of imminent peril — the threat of a brutal scalping by the vengeful "natives." Fear and uncertainty swirled in the American soldiers' eyes, and in their desperation, they laid down their arms and surrendered. What appeared to be an impending clash of might had been masterfully transformed into an act of wits, guided by the captain's deft hand.

Thirteen American soldiers, who had ventured with the intent to conquer, now found themselves transformed into captives. Bound by the threads of deception and outwitted by an ingenious stratagem, they were led to the city of Kingston, their destiny forever intertwined with the sagas of history.

The legacy of the 84th Regiment reverberates through time, woven into the very fabric of Prince Edward County's history. Over two centuries may have passed since their arrival, yet the echoes of their bravery and resilience continue to resound in the land they helped shape.

As you peruse the list of officers, non-commissioned officers, and men of the 84th Regiment and their affiliated corps who found their home in Prince Edward County, take a moment to trace the threads that connect past and present. Their legacy is not confined to history books; it lives on in the lives they helped forge and the County they helped cultivate.

- R. N. Y.- King’s Royal Regiment of New York (Sir John Johnson’s Corps.)

L. R.- Loyal Rangers (Jessup’s Corps.)

K. R.- King’s Rangers.

O. R.- Orange Rangers. E.R. Butler’s Rangers.

| Campbell, Richard | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Chavassey, James | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Corbman, Jacob | Sophias & Ameliasb’g | R. R. N. Y., Sergeant |

| Cryderman or Cruderman, Michael | Marysburgh | R. R. N. Y. |

| Cummings, John | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Downley or Downey,Conretius | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Dulmadge, David | Marysburgh | L. R. |

| Edwards, James | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Farrington, Robert | Marysburgh | R. R. N. Y., Corporal |

| Fox, Frederick | Sophiasburgh | R. R. N. Y., Corporal |

| Frederick, Lodwick | Marysburgh | R. R. N. Y., Corporal |

| Grant, John | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Grant, James | Marysburgh | 84th, Sergeant |

| Hicks, Benjamin | Marysburgh | B. R. |

| Howell, John | Sophiasburgh | R. R. N. Y., Sergt. Major |

| Kelly, Patrick | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Lodwick, Frederick | Marysburgh | R. R. N. Y. |

| MacDonnell, Archibald | Marysburgh | 84th Lieutenant |

| Mugel, Gadless | Sopias & Ameliasb’rg | R. R. N. Y. |

| McCrimmon, Donald | Marysburgh | 84th |

| McKenzie, William | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Ogden, John | Marys & Sophiasb’g | R. R. N. Y |

| Peters, John | Marys & Sophiasb’g | L. R. Ensign |

| Porter, Timothy | Marys & Sophiasb’g | L. R. |

| Powiss, Edward | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Price, Thomas | Marysburgh | K. R. |

| Richards, Owen | Marys & Sophiasb’g | R. R. N. Y. Sergeant |

| Roberts, Thomas | Marysburgh | R. R. N. Y. |

| Ross, Walter | Marysburgh | 84th, Sergeant |

| Saunders, Henry | Marysburgh | K. R. |

| Stewart, John | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Sutherland, John | Marysburgh | R. R. N. Y. |

| Wright, Joseph | Marysburgh | 84th |

| Young, Daniel | Marys & Sophiasburg | R. R. N. Y. |

| Young, Henry | Marys & Sophiasburg | R. R. N. Y. Lieutenant |

| Zufelt, Henry | Hallowell | L. R. |

As it happens, Col. Henry Young is my maternal ancestor (going back 7 generations). His sons, Daniel and Henry Young Jr. , are included in the above list. Henry was awarded 3,000 acres at East Lake in recognition of his service to the British Crown during the American War of Independence. It is said that Fort Henry at Kingston was named after Henry Young.

Today, their stories endure, handed down through generations, each family name like a thread interwoven into the tapestry of Prince Edward County’s past. These Highlanders, who once marched on distant battlegrounds, found a second home in this tranquil land, nurturing families whose roots run deep.